Picture the Great Depression.

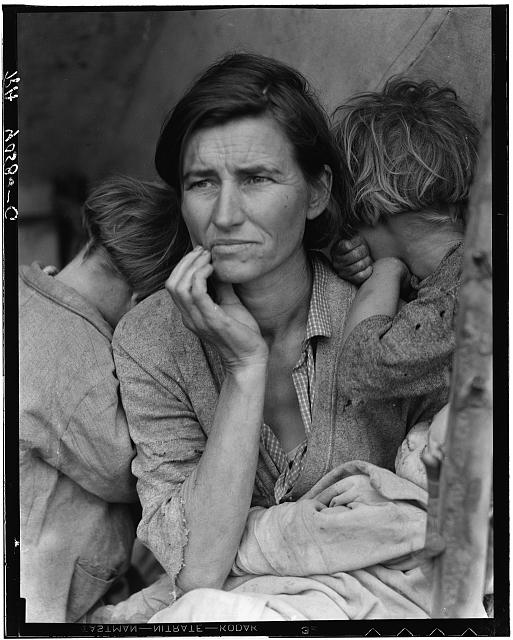

You probably didn’t live through the 1930s, and yet, for most of us, clear image comes to mind when we think of this era. Men stand with signs around their necks protesting the crippling levels of unemployment, begging for relief. Families on dilapidated porches. A mother, dirt etched into the worry lines on her face, holds a young child to her chest. Our collective memory of the Great Depression is so strong it is almost as though this era was lived in black and white.

If the Great Depression had a face, it would be Florence Owens Thompson, better known as Migrant Mother. This iconic photograph was captured by Dorothea Lange in 1936. She captioned the image, “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California.”

When this photo was taken, Lange was working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), under Roy Stryker. She was on assignment to capture the migrant labor crisis in California. The FSA, which was initially called the Resettlement Administration, was new agency formed by the newly elected Roosevelt administration, to help address the problem of rural poverty. Roy Stryker was hired to lead its Information Division.

His task was to create an extensive photo collection documenting the experiences of rural Americans during the Depression. He was told to “Show the city people what it’s like to live on a farm and remember, even though people are hungry and without work, wearing ragged clothes and old shoes, they’re still important human beings.” (qtd in Wetzel 260). Though the project was documentary in nature, it was also highly political. Stryker, and the Roosevelt administration, were interested in presenting a picture of American poverty as the consequence of former economic policies, rather than character failings, in order to promote Roosevelt’s “New Deal” policies.

Stryker and the FSA saw photography as “a simple and unspectacular attempt to give information . . . to confront the people with each other . . . in order to promote a wider and more sympathetic understanding of one for the other” (internal FSA documents qtd. in Wetzel 260). Stryker insisted that his photographers be well read on the regions they were sent to, and often assigned them specific documents to read (Finnegan 46). He would often also provided them with detailed “shooting scripts” that listed the themes and images the FSA was most interested in at the time. One “script” from 1942 asked for “pictures of rubber tires and scrap metal for recycling, automobiles in used car lots, and signs that suggested the effects of the war,” as well as photographs of people who appeared “as if they really believed in the US” (Finnegan 43).

Between 1935 and 1942, Stryker’s photographers – including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and Ben Shahn – captured over 250,000 images, approximately 170,000 of which were preserved in the Library of Congress, where they are still available today. Yale University has also created a digital tool mapping the FSA images to where they were taken. The project, Photogrammar, allows the audience to visualize the collection’s the distribution by county or by photographer.

Finnegan, Cara A. Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2003.

Wetzel, Alissa C. “New Deal Photographs of the Hoosier State Farm Tenancy, the Great Depression and the Young Girl Who Lived Through It All.” Indiana Magazine of History 109 (2013): 257-74.

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven children without food. Mother aged thirty-two. Father is a native Californian. Nipomo, California. Feb. or Mar, 1936. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/fsa.8b29516/>.