[The] punching of holes through negatives was barbaric to me… I’m sure that some very significant pictures have in that way been killed off, because there is no way of telling, no way, what photograph would come alive when.

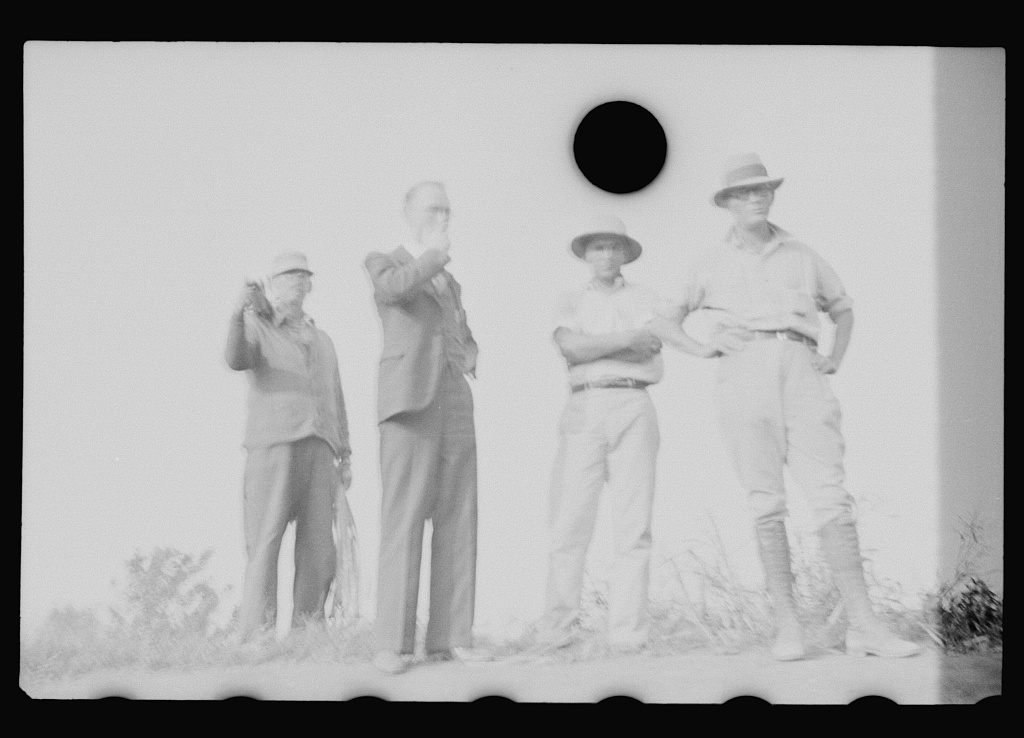

The “killed negatives” are negatives within the FSA’s Black-and-White Negatives collection, that have had a circle hole-punched out of them, leaving a solid black dot when the image is printed. These dots, which mark thousands of photos, are the result of Roy Stryker’s – at times – ruthless editing style, wherein he would hole-punch through the negatives of images he did not wish to be published. Stryker offered no explanation of why he chose to kill the photos he did. In a recent Mashable article on the killed negatives, postulates “Perhaps an image was redundant or poorly made. Perhaps it failed to convey a socioeconomic truth. Perhaps Stryker wanted to push his shooters to work more thoughtfully. Or perhaps he was in a bad mood.” Cara Finnegan take a more measured approach in Picturing Poverty, claiming Stryker mostly killed that were “technically flawed in obvious ways” (Finnegan 51). Whatever the case may have been, one thing is clear: as the program director and gate keeper, Stryker had absolute power, throughout most of the 1930s, over which images could be published and which could not.

Whether his intention or not, Stryker’s hole-punch acts as a tool of erasure, removing small sections and details from the images and leaving behind empty space. This empty space prints solid black when the photo is developed. But, because it is impossible to create an image from these negatives without the black dot, we can Stryker’s “killed negatives” as having the presence of a black dot, rather than the absence or erasure of content.

They are “killed negatives,” impart because they produce commercially dead images. Whichever framework we used to understand these images, it is important to remember that they were never intended to be published. The purpose of “killing” negatives was to ensure they would produce commercially dead images. That this project focuses on killed negatives and treats them as a valuable subset of the FSA collection is, in effect, a challenge to Stryker’s initial project and control.

Even when Stryker was not killing their negatives, his editing style and the FSA process was taxing for his photographers. Without the means to develop their film while traveling, many of the photographers would send their raw film directly to Stryker, thus the first time they would see their images was when Stryker would mail them prints requesting captions, after he decided which photos would could be published and which would be killed (Finnegan 50). Arthur Rothstien, an FSA photographer, wrote to Stryker in 1939, “If you only knew how important it is to a photographer in the field to receive frequent information about his work. He may take pictures for days only to discover after he had spoiled or marred many shots that there was a slight defect he could have corrected” (qtd. in Finnegan 50-51).

After extensive complaint from his staff photographers, Stryker eventually changed his editorial policies. Instead of killing “unsuitable” negatives upfront, he would send of complete copy photographers prints to them in the field and he would tear the corner off prints of negatives he believed should be killed. Phtographers continued to write captions for the photos Stryker requested, but this new editorial process allowed the photographers to express their disagreement with Stryker’s choices, prior to having their negatives irrevocably damaged.

Finnegan, Cara A. Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2003.

United States Resettlement Administration, photographer by Shahn, Ben. [Untitled photo, possibly related to: Tomb painter in cemetery at Pointe a la Hache, Louisiana]. [Oct, 1935] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa1997016516/PP>.

United States Resettlement Administration, photographer by Lee, Russell. [Untitled photo, possibly related to: Residents of Winton, Minnesota]. [Aug, 1937] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa1997021937/PP>.