There is a word-art relationship present in the FSA’s collection, even before I, and other scholars, begin to engage critically and creatively with it. This relationship is primarily between the the images and the captions they were given by photographers. Some photographers, motivated by the knowledge potential captured in their images, also submitted supplementary written material with their negatives, to be catalogued and available to government officials or journalists using FSA photos in their publications. Though Stryker had a clear political motive in how he directed the work of his photographers, he also recognized the potential historical value of his project. In 1937, he wrote to Dorothea Lange (qtd. in Finnegan 47),

“There are still times that I am surprised that we have been permitted to do as much photographing of the United States as we have… I feel certain that someday it will be a more important record than it now seems at the moment.”

Lange, herself, was one of only a couple of the FSA photographers who would include thorough field notes and photo annotations with the film she submitted to Stryker. In her book American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, a documentary collection of photos and reflections on rural American poverty in the 1930s, she wrote, “I dont like the kind of written material that tells the person what to look for, or that explains the photograph. I like the kind of material that gives more background, that fortifies it without directing the person’s mind. It just gives him more with which to look.”

In her independent publications, Lange could caption her photographs in whatever manner she desired, however, for with her work with the FSA only those photographs that Stryker deemed fit for publication received captions of any kind. Stryker’s hole-punching of negatives thereby disrupted the word-art relationship of these negatives. The black dot of his punched hole signals a double erasure of the subject – attacking both the image and the textual details that would otherwise accompany it.

Generally, the FSA photographs are so visually compelling, that reading the caption is secondary to examining the photo. Despite having been rejected the killed negatives are equally compelling in this way, to the extent that I almost do not mind being denied a caption, at least initially. Consider the two photos below.

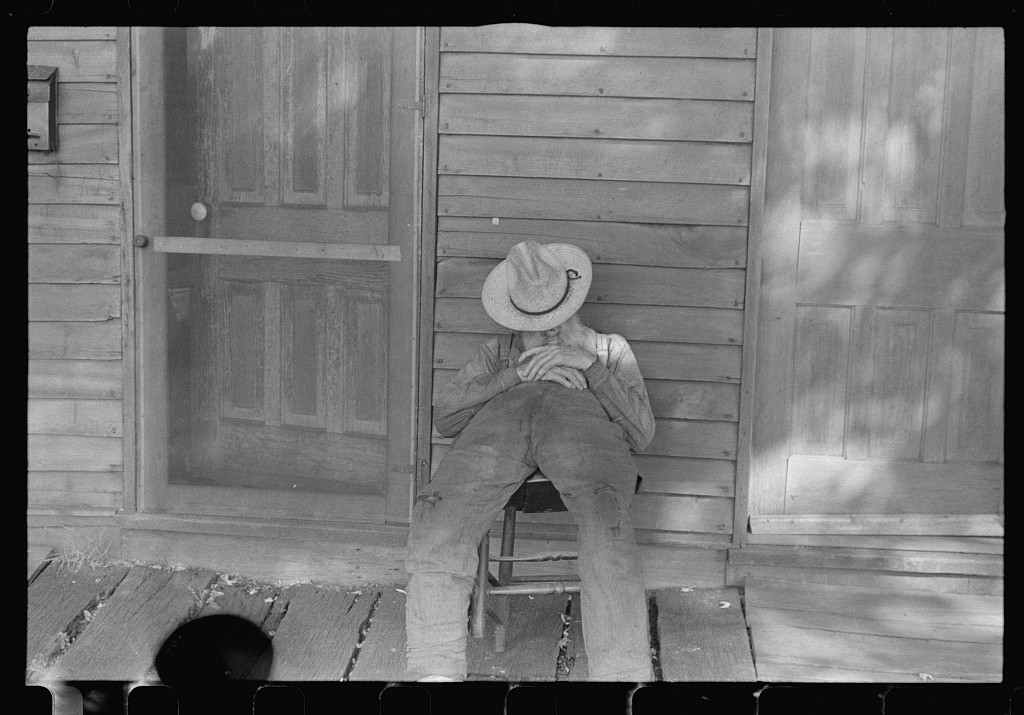

They are remarkably similar in content – both feature a man in work clothes and a hat that obscures his face, on the porch of a house. They are also very similar in composition – the man is centred in each and is famed by the house’s windows and doors. Both have been marked by Stryker’s hand, though in different places. They are both intriguing photos, and without captions, they could be presumed to tell similar narratives. But when words are added, our understanding of the two images diverges. Consider them both again.

Circleville, Ohio’s “Hooverville” (see general caption). Begins to talk: “No man in the United States had the trouble I had since 1931. No man. Don’t talk to me. I’m deaf. I lost my farm in 1931. I went to work in an acid factory. I got acid spilt on me; burnt my nose and made me blind. Then I get those awful headaches. I’ve been to lots of doctors, but that doesn’t help me. They come on at sundown. No man in the United States had the trouble I had since 1931.” (This last repeated many times through his talking.) “No man. It must be getting on to 6 o’clock now. My head’s beginning to pain.”

We know next to nothing about the context of the first image. No caption is given, not even one inferred by the archivists based on its surrounding images. No year is given, only the date range, 1935-1942, during which all the photographs in the FSA collection were captured. We know nothing about where the photograph was taken, except that we can assume from the toboggan in the image that it was taken in the North, where it snows. We do not even know who took the picture. Typically it would be possible to infer some of this information by looking at the photographs with similar call numbers, however, in the archive this image is surrounded by similarly untitled, undated, credit-less images.

By contrast, the Library of Congress archive includes more about the second image than any other killed negative have I found. It was taken by Ben Shahn, in Circleville Ohio, during the summer of 1938. We do not know the subject’s name, but based on the caption it seems he may have intentionally wished to remain anonymous. We are, however, told a lot about the subject: his face is acid burned from a factory accident, he is blind and deaf, he can no longer work and experiences chronic pain.

Comparing the photos initially, it may have seemed like this man was lazy, or at the very least taking a rest, whereas the other man is working, moving a large agricultual sack. But with the caption, suddenly, the sitting man is not simply resting, but actively being kept from work by factors beyond his control. We cannot see his face and thus must take his word, and Shahn’s, that his face is burned. The man’s agency, however limited, is revealed in his choice to conceal his face from the camera. Without the caption, I would assume Shahn positioned or directed the man in that way, but based on the caption and his unwillingness to engage in dialogue with Shahn, I am forced to reread the photo in a way that will acknowledge the man’s right and ability to make choices.

Beyond the fact that it exists with a killed negative, this caption is particularly remarkable because it captures the subject’s voice and actively humanizes him. The word-image relationship for this photo, particularly in the use of dialogue, is reminiscent of Human’s of New York. Even more remarkable is that this photo was part of a series, and Shahn also offers a “general caption” for the series:

“Circleville, county seat of Pickaway County. Average small Ohio city, depending upon surrounding rich farmlands for its livelihood. Because of its non-industrial surroundings, retains much of old-time flavor. Outstanding industries: Eshelman’s Feed Mill. Employs 150-200 men the year ’round. Pay averages about eighty-five cents an hour. Container Corporation of America makes paper out of straw, can absorb by-product of all neighboring farms. In addition, a number of canneries and feed mills. During depression many farms of the district were foreclosed. People who lost homes naturally gravitated toward the town. A town of its character is unable to house new influx of population. Consequently there sprang up around it an extensive Hooverville. Circleville got its name through having been built in a circle as a better protection against the Indians. For further information Chamber of Commerce, Circleville. Circleville is the home of Ted Lewis.”

All of the photos in the FSA collection were taken during the Great Depression; all of the photos’ subjects suffered to some extent. But this killed negative’s caption provides an particularly detailed incites into this man’s suffering that are not possible with other, uncaptioned, killed negatives. Which man do you, can you, empathize with more? If the FSA photographs were intended to present American poverty a consequence of the previous government’s failed economic policies, rather than the result of flawed character, which of the two photographs – with accompanying text – is more successful?

Finnegan, Cara A. “Documentary as Art in ‘US Camera’.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 31 No. 2 (2001): 37-68.

[Untitled]. [Between and 1942, 1935] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa1997001483/PP>.

Shahn, Ben, photographer. Circleville, Ohio’s “Hooverville” see general caption. Begins to talk: “No man in the United States had the trouble I had since 1931. No man. Don’t talk to me. I’m deaf. I lost my farm in 1931. I went to work in an acid factory. I got acid spilt on me; burnt my nose and made me blind. Then I get those awful headaches. I’ve been to lots of doctors, but that doesn’t help me. They come on at sundown. No man in the United States had the trouble I had since 1931.” This last repeated many times through his talking. “No man. It must be getting on to 6 o’clock now. My head’s beginning to pain.”. Summer, 1938. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa1997018627/PP>.